Neither we, nor seeds, may always choose where we land.

The Fox and I dart southwest into Monmouthshire, the kind of place where paths do not reveal themselves to Google maps; the nine-eyed car won’t go this far, and their satellites frustrated by the holloway roads who make themselves known through our tyres.

Needling down the border, missing left turns and slowing round corners, making and unmaking session plans as I cogitate over the power eco-poetics has wielded on my own life and what of this I wish to distil for the group with whom I will spend the most part of the afternoon.

I have perfected the art of navigating blind to voice notes while driving, so I need not pull over to recall the poetry that arises from watching the road, its entangled verges and ecotone. All the things I have noticed this season, turning the poet’s eye, the child’s eye, to the world, asking myself how I feel, asking why.

This month, it is the dead: creatures becoming carrion, sinking into the road, through a combination of natural, and unnatural processes. Insides, trailing outside, bodies curled and vulnerable. Shooting season, natural migrations and other disturbances forcing small creatures to cross brutal and winding grey roads.

Today, as all days, I am a poet, and also, today, a participant. We are at the Grange Project, marking the midpoint between the Wye Valley and the Bannau Brychieniog, and we are doing some small work to finish the job begun by the project’s late Saddleback pair. The pigs, shifting, rootling and tearing up the thick mat of impenetrable grass over the summer, have been moved on to interdimensional pastures new, and that’s where we come in, an intrepid band of budding ecologists, conservationists, Young Wilders, armed with handfuls of seed from a Gwent Wildlife Trust-managed farm down the road.

Noah and Meg providing the backstories of the diligent piggies

In the tangle, it is still easy to mark where the pair had done their work, and we set to the ground, kicking, scuffing, and raking with bare hands, the dying clods of grass to make space for the seeds, and deeper seed store, to open up the soil.

Poetry begins, unsurprisingly, with rich red dirt pushing at the skin under your fingernails.

After lunch, we settle to write. I am of the firm belief that ecologists are natural born poets, for the fundamentals, an innate curiosity, an openness to the world, a relentless how and why and wonderment, are already there. It is, as ever, a question of channelling this into language as a mode of exploration and enquiry.

Poets, hard at work.

The session plan I have made and unmade, remakes itself again as we discuss together what we have noticed this season, today, about the world immediately before us, how we respond to it. We capture these things, we breathe character into them, exploring how things look, sound, feel – whether tactile, or animistic. The features of our shared day begin to resound and mythologise under the high ceilings of the Grange. An elegy to the Saddlebacks brings sharp tears to my eyes and the tip of my nose. As responsible participants in an ecosystem we break down notions of individualism in art, borrowing each others’ lines to respond to, to metabolise and to transform.

Hunting torn turf, ripe for sowing.

Finally, we explore the relationships across the botanical lifecycle, taking the humble seed, its journey and its predators and conspirators, to find metaphors for human experience. These are channelled into one final exercise, of a collaborative poem existing across poets, notebooks, some stanzas read aloud, some left silent, some left as ideas that may, or may never, see the light of way. And all of it–

is poetry.

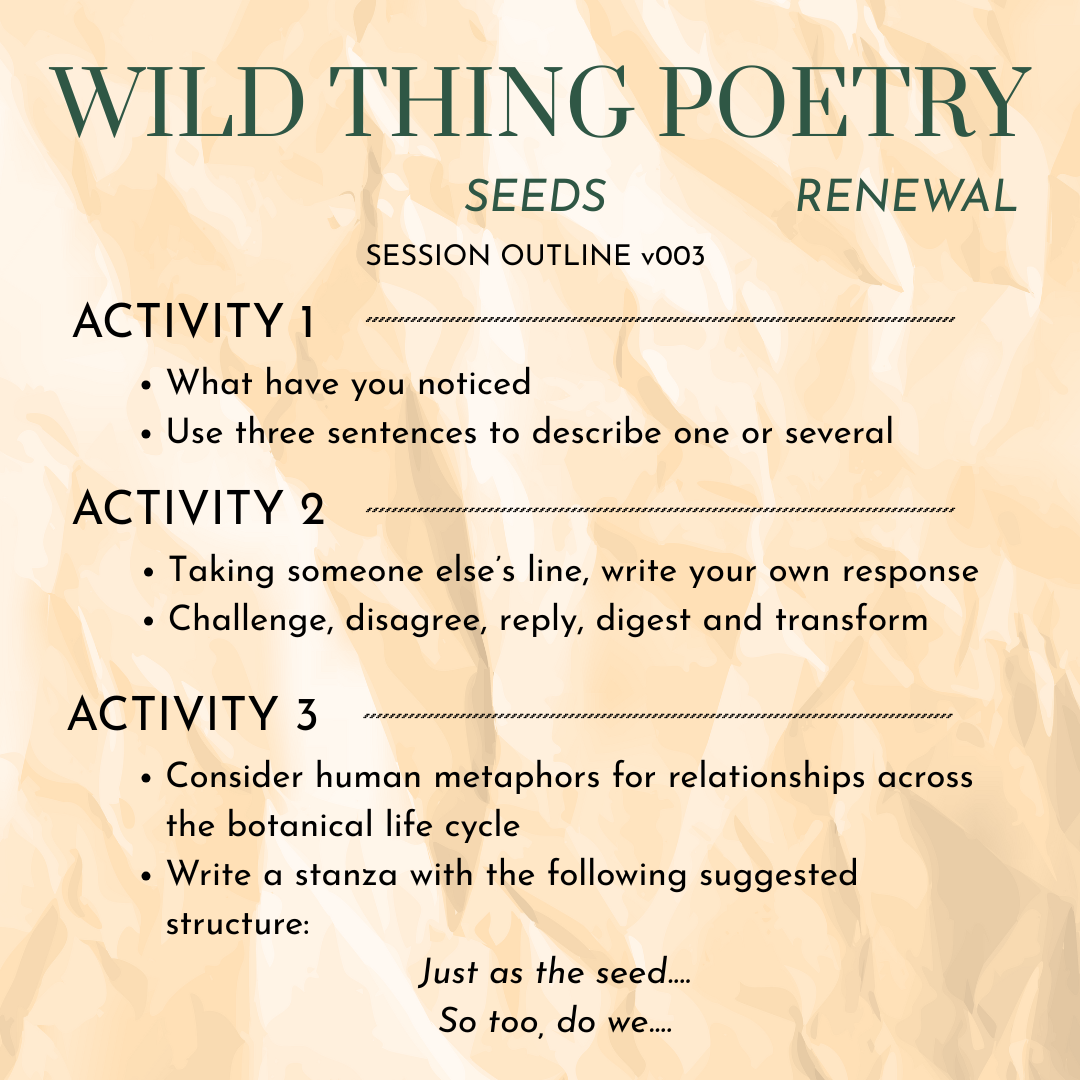

The final session outline, more or less.

With many thanks to Meg and Noah of the Young Wilders team for having us along!